Special to the Armenian Weekly

Tehmine Martoyan is lecturer at the University of Economy and Law (Yerevan, Armenia). She is also the president of Lazaryan Institute scientific and educational NGO.

Martoyan is the author of books and articles on the Armenians in Safavid Iran, and she has participated in international conferences and meetings in Armenia and abroad. She also translated into Armenian the book by Theofanis Malkidis titled The Greek Genocide: Thrace, Asia Minor, Pontus.

She has made two films dedicated to the Greek and Armenian populations in Smyrna. Her forthcoming book is titled Psychological and Political Causes of Annihilation of the Armenians and the Greeks in Smyrna.

This interview was conducted by email during early Sept. 2017.

***

George Shirinian: You contributed the chapter in Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, 1913-1923, titled “The Destruction of Smyrna in 1922: An Armenian and Greek Shared Tragedy.” Amid all the chaos and destruction at that time, why is the fate of this one city noteworthy today?

Tehmine Martoyan: First of all, I would like to express gratitude for the opportunity to commemorate with the readers of this journal the 95th anniversary of the destruction of Smyrna, which began on Sept. 13, 1922. Smyrna was a major international commercial center, and it was also known as a tolerant and cultured place, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims had lived together in harmony and prosperity, before the advent of extreme Turkish nationalism.

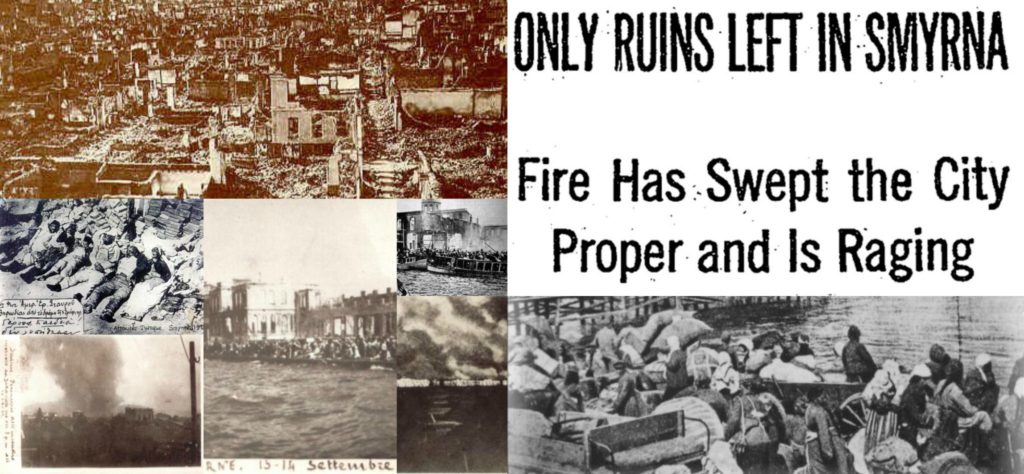

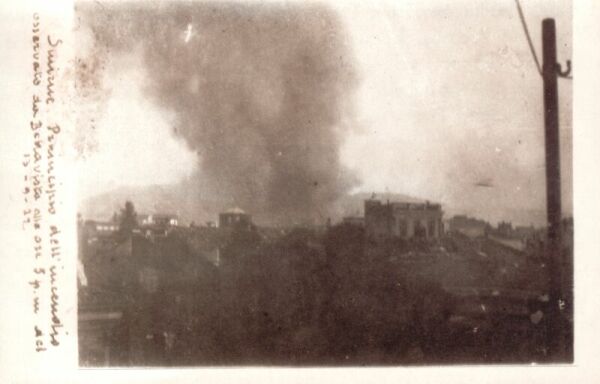

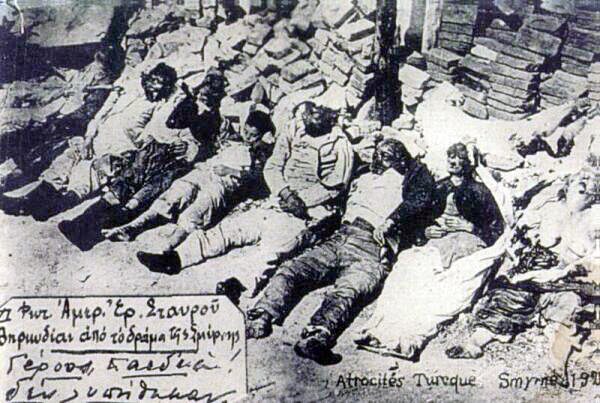

The Allied Powers suspected Ataturk was going to take reprisals on the city for the conduct of the Greek army during the Greco-Turkish war, and warned him against doing so, but he ignored their warning and got away with it. It was an unnecessary act of wanton destruction that affected only the Christian sections of the city. What happened is very well documented, by eyewitness accounts, photographs, and even video.

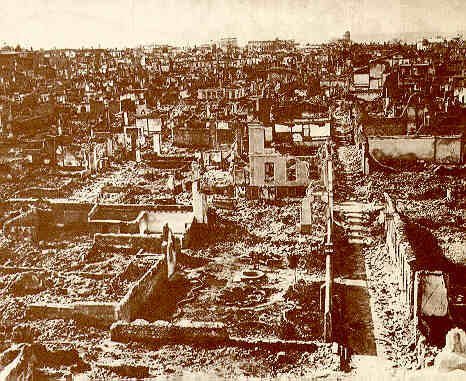

The extermination of the Armenian and Greek people of Smyrna and the destruction of the Christian districts of the city made a great impression on contemporaries and continues to attract the attention of researchers today. Entire books are still being written about it.

G.S.: Explain briefly what happened.

T.M.: One author has described the event this way: “What happened over the two weeks that followed must surely rank as one of the most compelling human dramas of the twentieth century. Innocent civilians—men, women, and children from scores of different nationalities—were caught up in a humanitarian disaster on a scale that the world had never before seen.” The Armenians and the Greeks of Smyrna were systematically robbed, murdered, and abducted.

According to the account of Edward Bierstadt—secretary for Near East Relief at the time—around 100,000 people fell victim to the slaughter, and 160,000 were driven away to the farthest parts of Turkey. More than 50,000 houses, 24 churches, and 28 schools, banks, consulates, and hospitals were burned. Turkish soldiers deliberately led the fire down the Greek and European sections of Smyrna by soaking the streets with petroleum or other highly flammable matter.

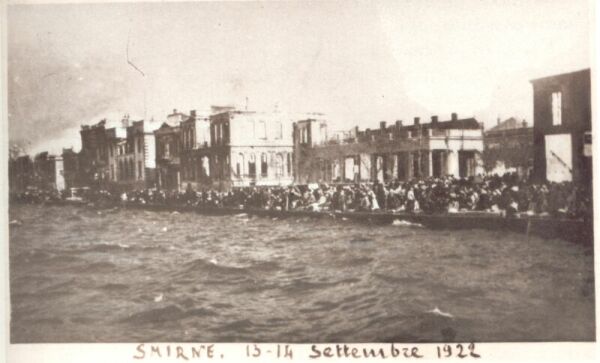

The people were massed along the quay, and with the fire and intense heat behind them; they had nowhere to go but jump into the Mediterranean. There were ships from several countries just outside the harbor, but most had orders not to intervene. Greek ships took refugees to the island of Mytilene and elsewhere, and a Japanese ship was noteworthy for joining the effort from the start, rescuing survivors from the sea.

The American navy helped only when the courageous Asa Jennings, a devout minister from upstate New York who had only recently arrived to take up duties as secretary to the local YMCA, rowed out to them and personally demanded that they rescue survivors. He was assisted by an equally courageous and strong-willed naval officer, Lt. Commander Halsey Powell. Together, they helped rescue almost a million refugees.

So, beyond the story of the destruction of the city and its non-Muslim population, there is the story of courageous rescuers who defied orders not to intervene.

G.S.: Why did Ataturk destroy this jewel of a city?

T.M.: To a certain extent it was to punish the Greeks for the Greco-Turkish War, even though the Smyrniotes were Ottoman citizens. But Smyrna was also a symbol of Christian prosperity, a major center of European trade, and an example peaceful coexistence between Christians and Muslims—all things the new Turkish nationalist movement was vehemently against. Ataturk even declared that neither American colleges nor any Christian institutions would operate in Smyrna in future. He wanted to build a new “Turkey for the Turks” out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire.

G.S.: Is there any parallel in history for such a destruction of a single city?

T.M.: The massacre in the Chinese city of Nanking (Nanjing) by the Japanese in 1937-38 comes to mind. It is interesting to note that the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia ruled that the murder of some 8,000 Muslim Bosnians in Srebrenica in 1995 was “genocidal.” One could say the same for the murder of 100,000 Armenians and Greeks of Smyrna.

G.S.: You mentioned that this history is particularly well documented. Are new sources still coming to light?

It is true that this history is particularly well documented, and there are new sources still coming to light. I am now researching the entire press of the period at the National Archives of Armenia and Fundamental library of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. I can also add that I had the opportunity to incorporate in my chapter a previously unpublished letter of the American eyewitness, Bertha Morley, from the Zoryan Institute archives.

G.S.: You have done extensive work on the Greek Genocide. Why do you, as an Armenian historian, devote so much attention to the Greek experience?

T.M.: Historical-cultural ties between the Armenians and the Greeks from ancient times are evident in their religion, culture, traditions, lifestyle, legends, etc. These two nations have always had strong ties, both emotionally and historically, due to religious and cultural roots.

Studying the experiences of these two peoples in parallel, I use content analysis as a research method to show how both the Armenians and the Greeks suffered from genocide that was planned and committed by the same state. As the subtitle of my chapter states, unfortunately the Armenians and Greeks have a shared tragedy.